10 cameras (har-prakash khalsa, bt#7)

"Rather than seeing technology as inherently good or bad, Jay shares a more nuanced perspective on how we can engage with our devices mindfully. [He] reveals how we can transform our relationship with technology to avoid compulsive habits and experience genuine connection in digital spaces."

—Scott Britton on EvolutionFM (watch or listen to the full episode)

Reclaim Your Mind: Seven Strategies to Enjoy Tech Mindfully is available now.

⭐ Already read it? Leave 5-stars on Amazon or Goodreads; it helps!

Hey all. It’s been a whirlwind of a week! Despite all the commotion, I managed to interview with Har-Prakash Khalsa, a wise and deeply trained meditation teacher (who offers retreats and coaching here). As you’ll see, even someone with no smartphone can have a beautiful dialogue with tech. -JV

JV: Hi Har-Prakash, I know you live mostly off-grid, but is there a technology that brings you joy, meaning or purpose?

HPK: Well, I have never used a smartphone. I do use computers but have never played computer games. But… I do have ten cameras of different formats, so that would be my tech.

JV: Oh, let’s dig into that. How do you relate to all these cameras?

HPK: I use the camera and the camera uses me. I consider both to be in the lineage of how something comes from nothing.

My relationship with photography has deepened and broadened over the years. When I was ten, I took my first photographs during a family camping trip to Killbear Provincial Park on Georgian Bay. The primordial beauty of the Precambrian shield rock and the surrounding landscape overwhelmed me, and I felt a strong urge to capture it.

I asked to borrow my father’s Kodak Instamatic camera, and he allowed me to take only a few photos because he said the film was expensive. Not wanting to waste any film, I spent considerable time exploring different ways to frame the landscape before pressing the shutter. During that focused process, the photographer within me was born.

Looking back, I realize I had entered a flow state, as described in positive psychology. This fully engaged attentiveness has consistently produced fulfilling flow experiences while I photograph. Attentiveness, or mindful awareness, has evolved into a contemplation and investigation of how perception affects the sliding scale of identity.

When I was thirteen, I saved money from my paper route and bought my first camera, a Yashica Electro 35. That same year, I met a friend who had a home darkroom, and we spent many hours making photographic prints together. Watching an image slowly form on a blank white paper submerged in liquid in a developing tray, transforming from nothing to something, is always a wondrous experience.

Photographing saved me during my teenage years. It provided an outlet to engage with the world in ways I might not have otherwise experienced and kept me out of serious trouble for the most part. It allowed me to see the world in a magical light, express my unique vision, and, in a sense, rescue me from feeling trapped within myself. When I was behind the camera, I felt empowered in a way that I did not experience in my everyday life.

JV: Why do you have so many and what do you love so much about cameras?

HPK: Most of my cameras are from early on when using film ruled the day. The cameras are mechanical engineering marvels. Their lenses control how light enters the camera. The lens's focal length, the type and number of glass elements inside, and the various apertures and shutter speeds shape perspective. I love the ingenuity that went into their design and construction.

I bought each camera for specific photography projects because they did what was best suited to my vision. At least that's what I told myself with each subsequent purchase… *laughs*

JV: Is there something you’ve figured out going deep with photography that might benefit how the rest of us use our cameras or think about photos?

HPK: We often take our ability to see for granted. What we see is a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Furthermore, humans interpret and value what we see differently, and we experience vision differently from other animals within that limited spectrum.

On a recent trip to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, my wife and I attended an exhibition about colour in the natural world. They featured an interactive slider on a screen that allowed us to compare the colors visible to humans with those visible to other animals.

Humans have red, blue, and green photoreceptive cones that combine to create the full range of colours we can see. In contrast, dogs have only two cones, which allow them to see only shades of blue and yellow. People with colour blindness also have only two cones and usually see mostly blues and greens. Birds have four types of photoreceptive cones, enabling them to see red, blue, green, and some ultraviolet light. Butterflies have five types of light-detecting cells, similar to photoreceptive cones, allowing them to see ultraviolet light most vividly.

Each of us is unique in how we see, what we see, and how we interpret our experiences. This process is miraculous, and when we use our cameras and take photographs, we can sometimes sense that we are participating in that miracle. When available, I highly recommend it.

JV: As a meditation teacher, you probably know about some of the issues and potential problems emerging with a lot of the mainstream tech out there. What do you feel like your relationship with photography can tell us about what a positive relationship with tech could be like?

HPK: Are we using technology meaningfully to help us pursue the good, the true, and the beautiful? Are we conscious of when our engagement with technology is wholesome, skillful, and guided by our core values?

Being wholesome and skillful doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy and have fun with our favorite tech; having fun can be very beneficial. Many people could benefit from enlightening up to replace their enheavyment.

A positive relationship with technology involves finding balance, fulfillment, and functionality. If our use of technology promotes the good, the true, and the beautiful for others, we earn extra bonus points.

JV: And what could your experience tell us about what it will take for humanity to use tech in better and more balanced ways now, in the near-term, and in the long-term future?

HPK: It comes down to discernment of how we use the tech and knowing more about how it uses us. Algorithms can free or enslave us. What happens when the external tech meets our internal programming? Victor Frankl’s famous quote from his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, is pertinent here:

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space.

In that space is our power to choose our response.

In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

Our power to choose our response has to be based on deep, universal values. Unfortunately, some people behind the tech haven’t coded their algorithms in the most ethical ways. The lack of ethical coding and transparency is concerning.

From deepfakes that misrepresent people to algorithms that silo people and prey on addictive tendencies, to criminal operations, to the hacking of algorithms, the list goes on. I wish there were a universal code that the programmers and AI programs adhered to and were held accountable to, something akin to the Charter for Compassion.

Who knows how AI will affect us in ways that are beyond our control? But where we have personal choice, let us choose how we engage with tech, knowing how it affects ourselves and others for better and worse.

Beyond whatever the external tech brings, if we can train and attain some of what the contemplative traditions say is at the deep end of the pool, such as achieving sensorial literacy and a fundamental okayness independent of external conditions, then all the better.

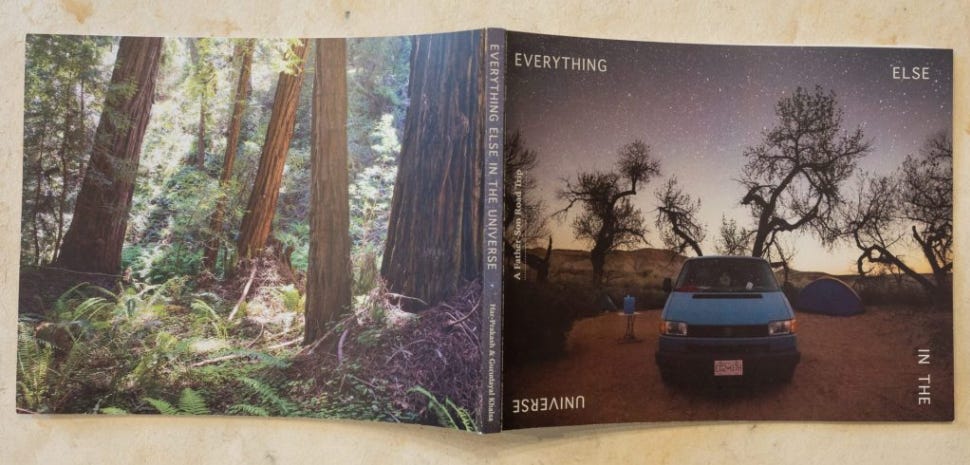

Har-Prakash also shared some of his photographs and a poem which I’ve included below. “The Hole Project” is gorgeous, evocative, and thought-provoking… the very meaning of new perspective.

JV: Before I let you go, I know some readers will want to know more about which specific cameras you have, what you like about them, and maybe you’d even be willing to share some photos?

HPK: My collection includes various cameras handling different film formats, ranging from 35mm to 6x6 cm, 6x9 cm, 4x5 inches, and 8x10 inches. I still have all of them except for a 4x5 GraflexSpeed Graphic camera, which I had to sell to pay my rent back when I was a student at art college.

Hmm. I also no longer have a favourite digital camera, the Fuji GFX 50R, a beautiful camera I could no longer use due to my worsening eyesight and inability to focus manually. But I can visit the camera, as I gave it to my son Gurudayal, also a photographer. Together, we created a photo book that you can view here.

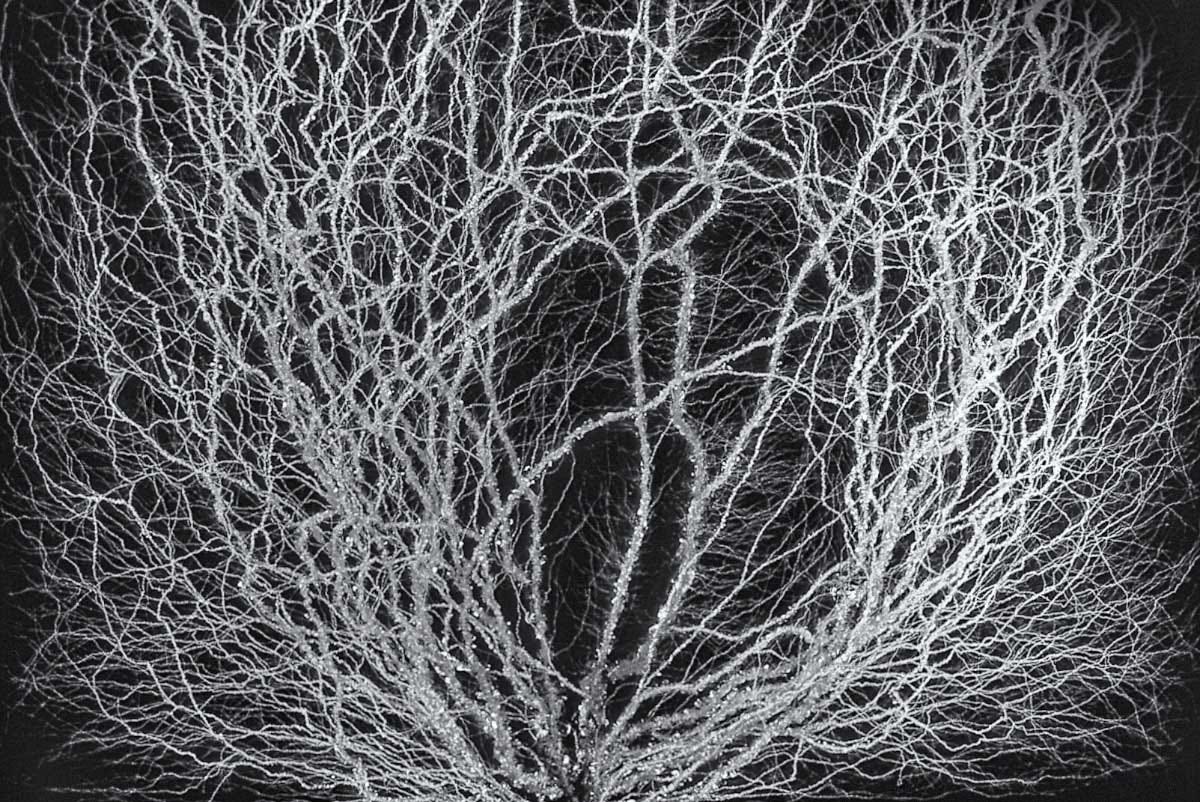

Some cameras I find a beautiful expression of human ingenuity at its best. One of my mechanical film favourites is the SL66 Rolleiflex from the 1960's. A glorious x-ray image of it graces the cover of The Camera, one volume of the seventeen-volume set published as the Life Library of Photography, which I own. The image reveals the mechanical parts hidden inside the camera’s shell. The SL66 allows you to reverse and retro-mount the lens for extreme close-ups. I used it to photograph the orifices of the human body for an exhibition called “The Hole Project,” which toured across Canada. You can see some of those results here.

Another remarkable camera is the Fuji 6x9cm Professional. The larger the film negative, the better the quality of the print. The capacity for detail increases alongside the range and subtlety of tonalities. I used this camera with a technical pan film, which has great detail but requires longer exposures. I used these features to create the “Motion Pictures” section of the “Infinite Pulse” series. I also utilized an old Burke & James Commercial 4x5 view camera for the “Sudden Flash of Lightning” images section of the same project. You can see those sections here.

I also own a handmade Phillips 8x10 view camera, a work of art from which I have never taken a photograph. I love looking at the care and craftsmanship that went into making it. Looking at the hyper-detail of an image on the ground glass under a dark cloth is an incredible experience. I can sense more detail is available on the ground glass than my eyes can process when seeing the world, which is a hyper-real experience.

Like the 4x5 cameras, the Phillips 8x10 operates as a view camera, taking one sheet of film at a time: 4x5 inches and 8x10 inches for those respective cameras. The image on the ground glass is upside down and backward, similar to how humans initially process visual imagery. Our retinas receive the inverted images from each eye. With assistance from the vestibular system in our ears, our brains process these two slightly offset visuals into one right-side-up image with depth. The mechanics of how we see are truly miraculous.

As a photographer, I see that view camera image upside down and backward and then imagine how it will look right-side up, as we usually perceive it. A similar process occurs when I look at film negatives. I can flip the tones and visualize the finished image.

These days, my many film cameras remain unused. I have a newer digital camera, the medium-format Fuji GFX 100-2, which has replaced all my film cameras. I can use most lenses from any era with this camera and have even created a custom lens from various components. I achieved an extremely shallow depth of field that produced the perspective I wanted for a specific project yet to be shared.

JV: Is there a story from your life that illustrates your relationship with technology?

HPK: I have a poem for you. You can hear me talking more about it here, but for now I’ll just share the poem itself: